George Boateng: An African Tech Pioneer in Switzerland

Selected by MIT Technology Review as one of its “35 Innovators under 35” for 2021, George Boateng is a pioneer of smartphone-based online coding education in Africa. He is also a doctoral candidate in applied machine learning at D-MTEC. We spoke with him about his educational and entrepreneurial journey and his experiences as a Black African in Switzerland.

George Boateng has been a problem-solving engineer since his high-school days. At the boarding school he attended in his home country, Ghana, students washed their own clothes and hung them on a line outside to dry. Too often, the clothes were stolen from the line. George, whose fascination with science had been awakened by an encyclopaedia he found in his grandmother’s house, was determined to improve this situation. He spent two years designing a portable electric clothes dryer. “I actually built it,” he recalls. “and it even worked – to some extent.”

When he graduated from high school, George says, “I really wanted to have an education where I could learn to build things. I knew I couldn’t get that in Ghana, so I decided to apply to universities in the US.” He was admitted to Dartmouth College, where he studied from 2012 to 2017, earning a BA in Computer Science, an MS in Computer Engineering, and a Business Training Certificate. He then remained at Dartmouth for a further year as a Research Scientist in the Computer Science department.

Social entrepreneurship

As an undergraduate at Dartmouth, George teamed up with a group of his high-school friends to found the external page Nsesa foundation (“Nsesa” means “change” in the Twi language of Ghana). In 2013, Nsesa launched a summer tech innovation boot camp for 15 Ghanaian high-school students. Nsesa’s ultimate goal is to spur an “innovation revolution” in Africa, in which young people across the continent develop solutions to problems in their communities using STEM.

In the first years of the programme, the students largely worked on donated laptops, but in time these broke down. In 2017, only a quarter of the new students had laptops of their own, and buying more would have overwhelmed Nsesa’s budget. At this point George practiced what he preached: innovation. All of the students had smartphones, so he and his colleagues redesigned the coding module to fit a five-inch screen.

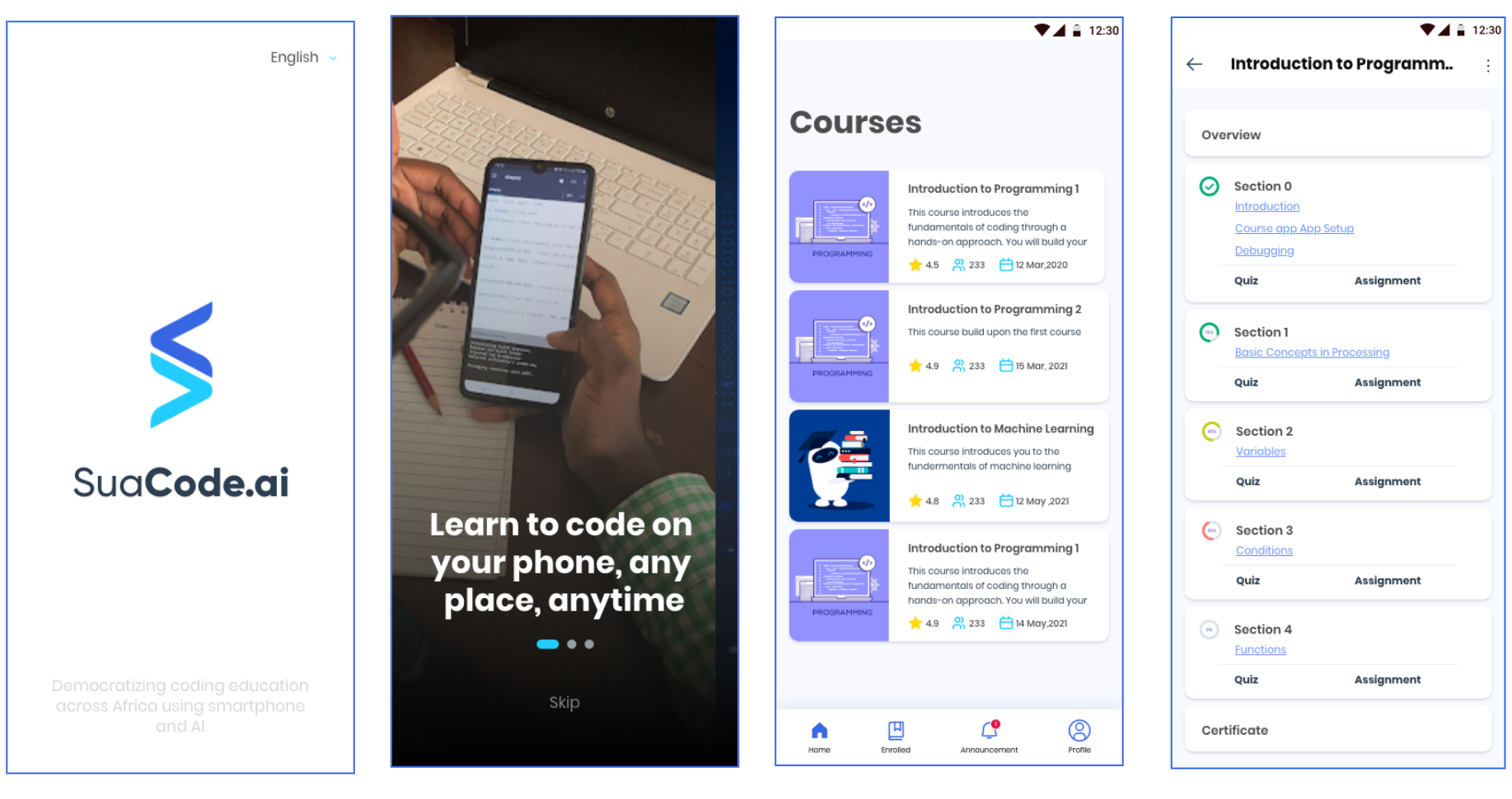

In 2018, George and co-founder Victor Kumbol ran their first pilot of external page SuaCode, an eight-week online smartphone-based course that already boasts hundreds of graduates from dozens of African countries. With so many students – and the goal of teaching millions more – the problem now became staffing the support forums. Once again, George had to innovate: he developed an English- and French-speaking AI-powered teaching assistant he called Kwame – a nod to Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah. “His pan-Africanist vision resonates with our goal of empowering youth across the continent,” George says. For his outstanding contribution to advancing tech education in Africa, George was named one of MIT Technology Review’s “35 Innovators under 35” for 2021.

Academic work

Given George’s focus on practical interventions, it might seem surprising that he is pursuing an academic career. But he notes that “all the research that I’ve done has been really practical. For example, for my undergraduate thesis, I built an app on a smartwatch to recognise whether students are stressed. And then for my Master’s, I collaborated with a physician to build a smartwatch app to monitor the physical activity of obese people. The idea was to intervene and help them lose weight.”

Serendipity brought George to ETH. “My advisor at Dartmouth was involved in a collaboration with a research group at D-MTEC. He found out about the doctoral opportunity, and forwarded it to me. It was a perfect fit.” George’s research at D-MTEC’s Chair of Information Management centres around emotion recognition in couples managing chronic disease, using data from smartwatches and smartphones.

“I use machine learning to analyse the data that we are collecting from these couples: proximity, heart rate, speech, and gestures,” George says. “So I’m leveraging computer science and engineering to solve real-world problems. It’s not just about publishing papers – it’s about impacting people. D-MTEC was created to make sure that technology is applied in the real world, so I feel really privileged to be here.”

Life in Switzerland: the good, the bad and the ugly

George’s experience in Switzerland, unfortunately, has been mixed. “There are a number of things I like about Zurich,” he says. “The first sentiment I had, coming from the US, was that Switzerland is calm. The transportation system is super – I can hop onto the tram or bus, and I know exactly when I’m going to arrive wherever I’m going. It’s amazing. And I’ve found a pretty good community. I have friends I like to interact with. So from that side, it’s been very good.

“But I also have to talk about the other side, which hasn’t been good. I recently had an experience in Geneva where a group of policemen rushed towards me and searched me as if I was a criminal. It wasn’t the first time that my African friends and I have been stopped by the police just for going about our normal activities, but now, after the experience in Geneva, I can’t stop thinking about it. It feels like Switzerland is a great place to live in terms of all the opportunities it offers, but it is bad, for example, if you are Black or from an African country – always being suspected, more likely to be stopped and asked for your permits.

“I want to be a professor. And even though ETH is a prestigious university and would be a great school at which to teach, if I’m going to continuously feel treated like a criminal in the country I live in, I may not want it.”

What ETH can do better

George notes with enthusiasm that ETH and its professors are engaged in initiatives, such as ETH4D (ETH for Development), that aim to improve life in many African countries. But he feels there is much that remains to be done within ETH’s own halls. “At Dartmouth, we knew what the percentage of Black people was. But here at ETH, I haven’t found any statistics about the number of Black people. If you don’t know that percentage, how can you work towards improving, say, the number of underrepresented minorities in STEM, or finding out what issues they are having and how to improve their situation?

“ETH is really proud of how international its student body is, which is great. But the questions are, what percentage of these people are from non-EU countries, or from the African continent? And are there things that stand as barriers in the way of people from African countries coming to ETH Zurich? One of these barriers is the application fee for Master’s programmes. 150 francs seems like nothing to most Swiss, but to many Africans it’s a prohibitive amount. Two of my friends who came to ETH from Ghana managed to apply only at a great personal financial cost. I think ETH could begin taking more steps towards investigating systemic things like that.”

“It’s important to have a racially diverse faculty. Seeing people who look like you informs how you see yourself in the future.”George Boateng

Why diversity?

George notes that he has had many conversations about the advantages of racial diversity for a university. “First and foremost,” he suggests, “it is always advantageous to have different perspectives, different experiences. It informs the kind of research that happens, and the output of that research. For example, I work on emotion recognition. And one of the things that I’m very careful about is not using facial data for emotion recognition, because there have been many studies in which machine-learning approaches have shown bias when applied to people with darker skin colour.

“This is just one example of how having people from different racial groups improves the quality of research by ensuring that it is fair – that it applies not just to people of a certain group, but to different kinds of people.”

“Another reason that it’s important to have a racially diverse faculty is that seeing people who look like you informs how you see yourself in the future. It is difficult to see yourself as an engineering professor if you don’t see a single engineering professor who looks like you. Having Black professors encourages people from underrepresented minorities to envision themselves as professors, as scientists.”

The future: plans and visions

Looking back on his journey so far, George Boateng connects it with his future: “Academia, industry, entrepreneurship, social impact – I’ve had the unique opportunity to experience each of these things. And the truth is, in the future, I want to do all of it.” He thinks he will be able to do this best as a professor.

Right now, George has just completed a 3-month internship at Amazon – working, naturally, with the emotion recognition group. As a visiting researcher at the University of Cambridge for the first half of 2022 he will further pursue his vision of a world “where we can leverage AI and mobile and wearable technology to improve health and remote education.” If the past provides any indication, George Boateng will play an important role in creating such a world.